How Was Ancient Rock Paintings Created

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/a2/cfa2b864-1c71-4b8e-9a1a-aa23b53b7517/janfeb2016_f09_indonesiacavepaintings.jpg)

I struggle to continue my ground on a narrow ridge of earth snaking between flooded fields of rice. The stalks, most set to harvest, ripple in the breeze, giving the valley the appearance of a shimmering green sea. In the distance, steep limestone hills rise from the ground, maybe 400 feet tall, the remains of an ancient coral reef. Rivers have eroded the landscape over millions of years, leaving behind a flat plain interrupted by these bizarre towers, chosen karsts, which are full of holes, channels and interconnecting caves carved by water seeping through the rock.

We're on the island of Sulawesi, in Indonesia, an 60 minutes'south drive north of the bustling port of Makassar. We approach the nearest karst undeterred past a grouping of large black macaques that screech at us from trees high on the cliff and climb a bamboo ladder through ferns to a cave called Leang Timpuseng. Inside, the usual sounds of everyday life here—cows, roosters, passing motorbikes—are barely audible through the insistent chirping of insects and birds. The cave is cramped and awkward, and rocks crowd into the space, giving the feeling that it might close up at any moment. But its minor appearance tin't diminish my excitement: I know this place is host to something magical, something I've traveled nearly 8,000 miles to see.

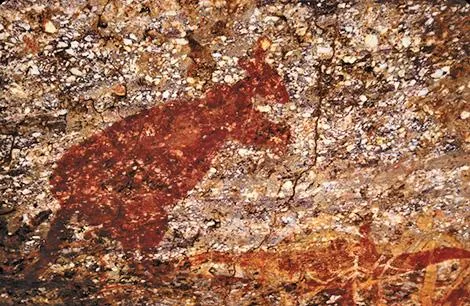

Scattered on the walls are stencils, man hands outlined confronting a groundwork of red pigment. Though faded, they are stark and evocative, a thrilling bulletin from the distant by. My companion, Maxime Aubert, directs me to a narrow semicircular alcove, like the apse of a cathedral, and I crane my neck to a spot nigh the ceiling a few feet above my head. Just visible on darkened grayish rock is a seemingly abstract blueprint of reddish lines.

And then my optics focus and the lines coalesce into a effigy, an animal with a large, bulbous body, stick legs and a atomic head: a babirusa, or pig-deer, once mutual in these valleys. Aubert points out its neatly sketched features in admiration. "Look, there's a line to represent the footing," he says. "There are no tusks—it's female. And at that place's a curly tail at the back."

This ghostly babirusa has been known to locals for decades, but it wasn't until Aubert, a geochemist and archeologist, used a technique he adult to engagement the painting that its importance was revealed. He found that it is staggeringly ancient: at least 35,400 years quondam. That likely makes it the oldest-known example of figurative fine art anywhere in the world—the world'south very outset flick.

Information technology's among more than a dozen other dated cave paintings on Sulawesi that now rival the earliest cavern fine art in Spain and France, long believed to be the oldest on earth.

The findings made headlines around the world when Aubert and his colleagues appear them in tardily 2014, and the implications are revolutionary. They boom our most common ideas about the origins of art and force united states to embrace a far richer picture of how and where our species first awoke.

Hidden away in a damp cave on the "other" side of the world, this curly-tailed beast is our closest link yet to the moment when the human mind, with its unique capacity for imagination and symbolism, switched on.

**********

Who were the first "people," who saw and interpreted the world as nosotros exercise? Studies of genes and fossils agree that Human sapiens evolved in Africa 200,000 years ago. But although these primeval humans looked like us, information technology'southward not clear they idea similar us.

Intellectual breakthroughs in human evolution such as tool-making were mastered by other hominin species more than than a million years ago. What sets u.s. apart is our ability to recollect and programme for the future, and to remember and learn from the past—what theorists of early human cognition call "higher lodge consciousness."

Such sophisticated thinking was a huge competitive advantage, helping united states of america to cooperate, survive in harsh environments and colonize new lands. It also opened the door to imaginary realms, spirit worlds and a host of intellectual and emotional connections that infused our lives with pregnant beyond the bones impulse to survive. And because it enabled symbolic thinking—our ability to let i thing stand for another—it immune people to make visual representations of things that they could remember and imagine. "Nosotros couldn't excogitate of fine art, or excogitate of the value of art, until we had higher gild consciousness," says Benjamin Smith, a rock art scholar at the University of Western Australia. In that sense, aboriginal fine art is a marker for this cognitive shift: Find early paintings, especially figurative representations similar animals, and you've constitute show for the modernistic human heed.

Until Aubert went to Sulawesi, the oldest dated fine art was firmly in Europe. The spectacular lions and rhinos of Chauvet Cave, in southeastern France, are commonly thought to exist around xxx,000 to 32,000 years old, and mammoth-ivory figurines found in Germany correspond to roughly the aforementioned fourth dimension. Representational pictures or sculptures don't appear elsewhere until thousands of years afterward. So information technology has long been assumed that sophisticated abstract thinking, peradventure unlocked by a lucky genetic mutation, emerged in Europe shortly afterwards modern humans arrived there about twoscore,000 years agone. Once Europeans started to paint, their skills, and their man genius, must accept then spread around the globe.

Just experts now challenge that standard view. Archaeologists in South Africa have found that the paint ocher was used in caves 164,000 years ago. They have also unearthed deliberately pierced shells with marks suggesting they were strung like jewelry, equally well every bit chunks of ocher, ane engraved with a zigzag pattern—hinting that the capacity for fine art was present long before humans left Africa. Still, the evidence is frustratingly indirect. Possibly the ocher wasn't for painting but for musquito repellent. And the engravings could have been one-offs, doodles with no symbolic meaning, says Wil Roebroeks, an adept in the archeology of early on humans, of Leiden Academy in the Netherlands. Other extinct hominin species have left similarly inconclusive artifacts.

By contrast, the gorgeous fauna cave paintings in Europe represent a consistent tradition. The seeds of creative creativity may have been sown earlier, but many scholars gloat Europe as the place where it burst, full-fledged, into view. Earlier Chauvet and El Castillo, the famous art-filled cavern in northern Spain, "we don't have anything that smacks of figurative fine art," says Roebroeks. "Merely from that point on," he continues, "you accept the full homo package. Humans were more or less comparable to you and me."

Yet the lack of older paintings may non reverberate the true history of rock fine art so much as the fact that they tin can be very difficult to date. Radiocarbon dating, the kind used to determine the historic period of the charcoal paintings at Chauvet, is based on the decay of the radioactive isotope carbon-14 and works just on organic remains. It's no practiced for studying inorganic pigments like ocher, a form of iron oxide used oft in ancient cave paintings.

This is where Aubert comes in. Instead of analyzing pigment from the paintings directly, he wanted to date the stone they saturday on, by measuring radioactive uranium, which is present in many rocks in trace amounts. Uranium decays into thorium at a known rate, then comparing the ratio of these two elements in a sample reveals its age; the greater the proportion of thorium, the older the sample. The technique, known as uranium series dating, was used to decide that zircon crystals from Western Australia were more than four billion years old, proving Earth'southward minimum age. Only it can likewise date newer limestone formations, including stalactites and stalagmites, known collectively as speleothems, which grade in caves as water seeps or flows through soluble bedrock.

Aubert, who grew up in Lévis, Canada, and says he has been interested in archeology and rock art since babyhood, thought to date rock formations at a minute calibration directly to a higher place and below ancient paintings, to work out their minimum and maximum age. To practice this would require analyzing nearly impossibly thin layers cutting from a cave wall—less than a millimeter thick. And then a PhD educatee at the Australian National University in Canberra, Aubert had access to a state-of-the-art spectrometer, and he started to experiment with the car, to see if he could accurately date such tiny samples.

Within a few years, Adam Brumm, an archeologist at the University of Wollongong, where Aubert had received a postdoctoral fellowship—today they are both based at Griffith University—started digging in caves in Sulawesi. Brumm was working with the late Mike Morwood, co-discoverer of the atomic homininHuman floresiensis, which once lived on the nearby Indonesian island of Flores. The evolutionary origins of this so-called "hobbit" remain a mystery, but, to have reached Flores from mainland Southeast Asia, its ancestors must have passed through Sulawesi. Brumm hoped to find them.

Every bit they worked, Brumm and his Indonesian colleagues were struck by the hand stencils and animal images that surrounded them. The standard view was that Neolithic farmers or other Stone Age people made the markings no more than v,000 years agone—such markings on relatively exposed stone in a tropical environs, it was thought, couldn't take lasted longer than that without eroding away. But the archaeological show showed that modern humans had arrived on Sulawesi at least 35,000 years agone. Could some of the paintings exist older? "We were drinking palm vino in the evenings, talking most the stone fine art and how we might date it," Brumm recalls. And information technology dawned on him: Aubert'south new method seemed perfect.

Afterwards that, Brumm looked for paintings partly obscured by speleothems every chance he got. "One twenty-four hour period off, I visited Leang Jarie," he says. Leang Jarie ways "Cavern of Fingers," named for the dozens of stencils decorating its walls. Like Leang Timpuseng, it is covered by small growths of white minerals formed past the evaporation of seeping or dripping water, which are nicknamed "cave popcorn." "I walked in andbang, I saw these things. The whole ceiling was covered with popcorn, and I could see $.25 of hand stencils in between," recalls Brumm. As presently as he got home, he told Aubert to come to Sulawesi.

Aubert spent a week the next summer touring the region by motorcycle. He took samples from five paintings partly covered by popcorn, each time using a diamond-tipped drill to cut a pocket-sized square out of the rock, about 1.v centimeters across and a few millimeters deep.

Dorsum in Australia, he spent weeks painstakingly grinding the stone samples into sparse layers earlier separating out the uranium and thorium in each 1. "You collect the pulverisation, and then remove some other layer, and then collect the powder," Aubert says. "You're trying to go every bit close equally possible to the pigment layer." And then he drove from Wollongong to Canberra to analyze his samples using the mass spectrometer, sleeping in his van exterior the lab then he could work as many hours as possible, to minimize the number of days he needed on the expensive motorcar. Unable to get funding for the projection, he had to pay for his flying to Sulawesi—and for the analysis—himself. "I was totally bankrupt," he says.

The very kickoff age Aubert calculated was for a hand stencil from the Cave of Fingers. "I thought, 'Oh, shit,'" he says. "So I calculated information technology again." So he called Brumm.

"I couldn't make sense of what he was proverb," Brumm recalls. "He blurted out, '35,000!' I was stunned. I said, are yous sure? I had the feeling immediately that this was going to be big."

**********

The caves we visit in Sulawesi are astonishing in their variety. They range from small stone shelters to huge caverns inhabited by venomous spiders and large bats. Everywhere in that location is evidence of how water has formed and changed these spaces. The rock is bubbling and dynamic, often glistening moisture. It erupts into shapes resembling skulls, jellyfish, waterfalls and chandeliers. Equally well as familiar stalactites and stalagmites, there are columns, curtains, steps and terraces—and popcorn everywhere. It grows like barnacles on the ceilings and walls.

We're joined past Muhammad Ramli, an archaeologist at the Eye for the Preservation of Archaeological Heritage, in Makassar. Ramli knows the fine art in these caves intimately. The outset one he visited, as a student in 1981, was a pocket-sized site chosen Leang Kassi. He remembers it well, he says, not least because while staying overnight in the cave he was captured by local villagers who thought he was a headhunter. Ramli is now a portly but energetic 55-year-sometime with a wide-brimmed explorer'due south lid and a collection of T-shirts with letters like "Salve our heritage" and "Go along calm and visit museums." He has cataloged more than 120 rock art sites in this region, and has established a organization of gates and guards to protect the caves from damage and graffiti.

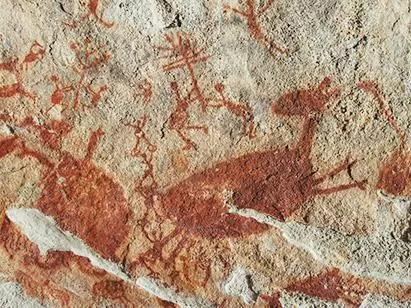

Almost all of the markings he shows me, in ocher and charcoal, appear in relatively exposed areas, lit by the sun. And they were apparently made by all members of the customs. At 1 site, I climb a fig tree into a small, high sleeping accommodation and am rewarded by the outline of a mitt and then modest it could vest to my 2-twelvemonth-erstwhile son. At another, hands are lined up in two horizontal tracks, all with fingers pointing to the left. Elsewhere at that place are easily with slender, pointed digits maybe created by overlapping i stencil with another; with painted palm lines; and with fingers that are bent or missing.

There's still a tradition on Sulawesi of mixing rice pulverisation with h2o to brand a handprint on the central pillar of a new house, Ramli explains, to protect confronting evil spirits. "It'southward a symbol of strength," he says. "Maybe the prehistoric man thought like that too." And on the nearby island of Papua, he says, some people express their grief when a loved one dies by cut off a finger. Perhaps, he suggests, the stencils with missing fingers indicate that this practice too has ancient origins.

Paul Taçon, an expert in rock fine art at Griffith University, notes that the hand stencils are like to designs created until recently in northern Australia. Ancient Australian elders he has interviewed explicate that their stencils are intended to express connection to a particular place, to say: "I was here. This is my home." The Sulawesi mitt stencils "were probably made for like reasons," he says. Taçon believes that once the leap to rock art was made, a new cognitive path—the ability to retain circuitous information over fourth dimension—had been set. "That was a major alter," he says.

There are ii main phases of artwork in these caves. A series of black charcoal drawings—geometric shapes and stick figures including animals such as roosters and dogs, which were introduced to Sulawesi in the last few thousand years—haven't been dated but presumably could not have been made earlier the inflow of these species.

Alongside these are red (and occasionally purplish-black) paintings that look very different: hand stencils and animals, including the babirusa in Leang Timpuseng, and other species endemic to this island, such as the warty pig. These are the paintings dated by Aubert and his colleagues, whose newspaper, published inNature in October 2014, ultimately included more than than l dates from xiv paintings. Near ancient of all was a hand stencil (correct beside the tape-breaking babirusa) with a minimum age of 39,900 years—making it the oldest-known stencil anywhere, and merely 900 years shy of the world's oldest-known cave painting of any kind, a uncomplicated red disk at El Castillo. The youngest stencil was dated to no more than than 27,200 years ago, showing that this artistic tradition lasted largely unchanged on Sulawesi for at least 13 millennia.

The findings obliterated what we idea we knew about the birth of human being creativity. At a minimum, they proved once and for all that art did non arise in Europe. Past the time the shapes of easily and horses began to adorn the caves of France and Spain, people hither were already decorating their own walls. Merely if Europeans didn't invent these art forms, who did?

On that, experts are divided. Taçon doesn't rule out the possibility that art might take arisen independently in different parts of the world after modern humans left Africa. He points out that although hand stencils are mutual in Europe, Asia and Australia, they are rarely seen in Africa at any fourth dimension. "When yous venture to new lands, there are all kinds of challenges relating to the new surroundings," he says. You lot accept to discover your fashion around, and deal with strange plants, predators and casualty. Possibly people in Africa were already decorating their bodies, or making quick drawings in the ground. Merely with rock markings, the migrants could signpost unfamiliar landscapes and postage their identity onto new territories.

Notwithstanding there are thought-provoking similarities between the earliest Sulawesian and European figurative fine art—the fauna paintings are detailed and naturalistic, with skillfully drawn lines to give the impression of a babirusa'south fur or, in Europe, the mane of a bucking horse. Taçon believes that the technical parallels "suggest that painting naturalistic animals is part of a shared hunter-gatherer exercise rather than a tradition of any detail culture." In other words, in that location may be something nearly such a lifestyle that provoked a common practice, rather than its arising from a single group.

Only Smith, of the Academy of Western Commonwealth of australia, argues that the similarities—ocher use, mitt stenciling and lifelike animals—can't be coincidental. He thinks these techniques must have arisen in Africa before the waves of migrations off the continent began. It's a view in common with many experts. "My bet would be that this was in the rucksack of the first colonizers," adds Wil Roebroeks, of Leiden University.

The eminent French prehistorian Jean Clottes believes that techniques such as stenciling may well accept developed separately in different groups, including those who eventually settled on Sulawesi. One of the world'south most respected authorities on cavern art, Clottes led research on Chauvet Cavern that helped to fuel the idea of a European "human revolution." "Why shouldn't they brand paw stencils if they wanted to?" he asks, when I reach him at his dwelling in Foix, France. "People reinvent things all the time." But although he is eager to encounter Aubert'due south results replicated past other researchers, he feels that what many suspected from the pierced shells and carved ocher chunks found in Africa is now all but inescapable: Far from existence a late evolution, the sparks of artistic creativity can be traced back to our earliest ancestors on that continent. Wherever you find modernistic humans, he believes, you'll find art.

**********

In a cavern known locally as Mountain-Tunnel Cave, buckets, a wheelbarrow and countless bags of clay environs a neatly dug trench, five meters long by iii meters deep, where Adam Brumm is overseeing a dig that is revealing how the isle'south early artists lived.

People arrived on Sulawesi every bit part of a wave of migration from eastward Africa that started around 60,000 years agone, likely traveling across the Red Sea and the Arabian Peninsula to present-day Republic of india, Southeast Asia and Borneo, which at the time was part of the mainland. To reach Sulawesi, which has always been an island, they would have needed boats or rafts to cross a minimum of 60 miles of ocean. Although human remains from this period haven't yet been found on Sulawesi, the isle'southward first inhabitants are thought to have been closely related to the first people to colonize Australia effectually 50,000 years ago. "They probably looked broadly similar to Aboriginal or Papuan people today," says Brumm.

Brumm and his squad have unearthed bear witness of fire-building, hearths and precisely crafted rock tools, which may accept been used to make weapons for hunting. Yet while the inhabitants of this cave sometimes hunted large animals such every bit wild boar, the archaeological remains prove that they mostly ate freshwater shellfish and an creature known equally the Sulawesi bear cuscus—a slow-moving tree-dwelling marsupial with a long, prehensile tail.

The French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss famously argued in 1962 that primitive peoples chose to place with and correspond animals non because they were "expert to eat" but because they were "practiced to think." For ice age European cave painters, horses, rhinos, mammoths and lions were less important as dinner than as inspiration. Ancient Sulawesians, it seems, were besides moved to depict larger, more daunting and impressive animals than the ones they often ate.

The hunt is now on for even older paintings that might have united states of america ever closer to the moment of our species' enkindling. Aubert is collecting samples of limestone from painted caves elsewhere in Asia, including in Borneo, along the route that migrants would have taken to Sulawesi. And he and Smith are too independently working to develop new techniques to report other types of caves, including sandstone sites common in Australia and Africa. Sandstone doesn't class cave popcorn, but the stone forms a "silica skin" that can be dated.

Smith, working with colleagues at several institutions, is only getting the first results from an analysis of paintings and engravings in the Kimberley, an area in northwestern Australia reached by modern humans at least 50,000 years ago. "The expectation is that we may meet some very exciting early dates," Smith says. "It wouldn't surprise me at all if pretty speedily we go a whole mass of dates that are earlier than in Europe." And scholars at present talk excitedly about the prospect of analyzing cave paintings in Africa. "99.ix percent of stone art is undated," says Smith, citing, every bit an example, ocher representations of crocodiles and hippos found in the Sahara, often on sandstone and granite. "The conventional date on those would exist 15,000 to xx,000 years old," he says. "But in that location'due south no reason they couldn't be older."

Equally the origins of art extend backward, we'll take to revise our oftentimes localized ideas of what prompted such artful expression in the beginning place. It has previously been suggested that Europe's harsh northern climate necessitated strong social bonds, which in turn nudged the development of language and art. Or that contest with Neanderthals, present in Europe until around 25,000 years ago, pushed modern humans to express their identity by painting on cave walls—ancient hominin flag-planting. "Those arguments fall away," says Smith, "considering that wasn't where information technology happened."

Clottes has championed the theory that in Europe, where fine art was hidden deep inside dark chambers, the primary function of cavern paintings was to communicate with the spirit world. Smith is besides convinced that in Africa, spiritual beliefs drove the very first art. He cites Rhino Cavern in Botswana, where archaeologists have constitute that 65,000 to lxx,000 years agone people sacrificed carefully made spearheads by called-for or smashing them in front of a big stone console carved with hundreds of circular holes. "Nosotros tin can be sure that in instances like that, they believed in some sort of spiritual strength," says Smith. "And they believed that art, and ritual in relation to art, could affect those spiritual forces for their ain benefit. They're not just doing it to create pretty pictures. They're doing it because they're communicating with the spirits of the country."

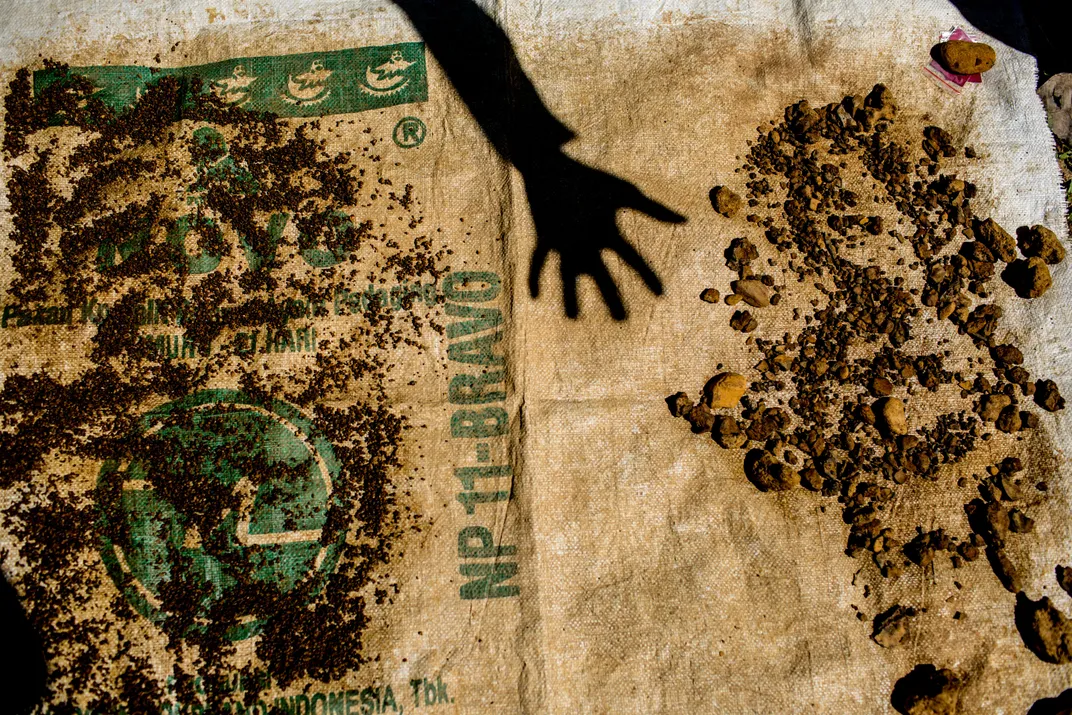

In Mountain-Tunnel Cave, which has manus stencils and abundant traces of paint on the walls, Brumm is now also finding the early on artists' materials. In strata dated to around the same fourth dimension as nearby stencils, he says, "at that place's a major spike in ocher." So far, his squad has establish stone tools with ocher smeared over the edges and golf game ball-size ocher chunks with scrape marks. There are also scattered fragments, probably dropped and splashed when the artists basis upward their ocher before mixing it with water—enough, in fact, that this entire slice of earth is stained cherry ruby-red.

Brumm says this layer of domicile stretches back at least 28,000 years, and he is in the process of analyzing older layers, using radiocarbon dating for the organic remains and uranium serial dating of horizontal stalagmites that run through the sediment.

He calls this "a crucial opportunity." For the first time in this part of the world, he says, "we're linking the buried bear witness with the rock art." What that evidence shows is that on this island, at least, cavern art wasn't always an occasional action carried out in remote, sacred spaces. If religious belief played a part, it was entwined with everyday life. In the middle of this cavern floor, the first Sulawesians sat together around the fire to cook, eat, make tools—and to mix paint.

**********

In a small subconscious valley Aubert, Ramli and I walk across fields of rice in the early morning. Dragonflies glitter in the sun. At the far edge, nosotros climb a set of steps high up a cliff to a breathtaking view and a cavernous foyer inhabited by swallows.

In a depression bedchamber within, pigs amble beyond the ceiling. 2 announced to exist mating—unique for cave art, Ramli points out. Another, with a swollen abdomen, might be meaning. He speculates that this is a story of regeneration, the stuff of myth.

Past the pigs, a passageway leads to a deeper chamber where, at caput height, there is a panel of well-preserved stencils including the forearms, which await as if they are reaching right out of the wall. Rock art is "one of the most intimate archives of the past," Aubert one time told me. "It instills a sense of wonder. We desire to know: Who made information technology? Why?" The animal paintings are technically impressive, just for me the stencils inspire the strongest emotional connection. Forty thousand years later, standing here in the torchlight feels like witnessing a spark or a birth, a sign of something new in the universe. Outlined by splattered pigment, fingers spread wide, the marks look insistent and alive.

Whatever was meant by these stencils, at that place tin can exist no stronger message in viewing them: We are human. We are here. I heighten my own paw to meet one, fingers hovering an inch in a higher place the ancient outline. It fits perfectly.

The Oldest Enigma of Humanity

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journey-oldest-cave-paintings-world-180957685/

Posted by: wolfwitur1946.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Was Ancient Rock Paintings Created"

Post a Comment